Saturday, November 29, 2014

Expressiveness in Games

It's difficult to talk about games in the abstract, in the sense of the ephemeral components that sum together with the concrete technology to produce video entertainment. Part of this is the relative newness of the medium, sometimes a game is great or terrible for reasons we don't yet have language to describe. These intrinsic qualities require a body of work to assess, so that patterns spring forth and we can start labeling those patterns.

Unlike how a Sommelier might call upon a rich descriptive lexicon to describe a wine, game reviewers have long struggled (and needed) to develop a vocabulary to describe a game to those who have not experienced it - to draw not just a visual picture with words, but an experiential image. A game might have "tight controls" or "loose controls" for example, with "tight" being perceptually better in most cases.

Unlike how a Sommelier might call upon a rich descriptive lexicon to describe a wine, game reviewers have long struggled (and needed) to develop a vocabulary to describe a game to those who have not experienced it - to draw not just a visual picture with words, but an experiential image. A game might have "tight controls" or "loose controls" for example, with "tight" being perceptually better in most cases.

Since the beginning. most games have been built around the idea of controlling an on-screen character or avatar. Derived from board game pieces, the game designers attempt to put your avatar into a variety of situations, relying on your shared identity and your instincts for self-preservation to spur you into action. During gameplay, you might be controlling a better-than-you-are Mario, capable of jumping, hopping, ducking, sliding, smashing, bouncing, stomping and otherwise careening about the play field in a dynamic controlled chaos - often using verbed moves in combination. Or you might be in charge of Duke Togo, capable of a saunter, a single height jump, and shooting while standing -- and that's it.

Putting on digital Mario, inhabiting him, you feel empowered, like you can do anything. As the game presents new situations, you feel like you have a toolbox of responses you can use to deal with them. Two different players might even approach the same part of the game with completely different approaches.

Poor Duke, however, feels like walking around a city wearing a refrigerator box while trying to maintain balance on a pogo stick. You feel panic at almost every encounter because your options are so limited: jump in mad desperation or stand there and absorb bullets until one of your wild shots finds a bad guy.

Mario allows you to express yourself, Duke doesn't. The game forces you to inhabit a hopelessly outclassed character, while Mario can be virtuosically played in any number of ways. Mario is an expressive character - and it's this expressiveness that defines the entire series to this day.

It's funny how often the presence of such an avatar can correlate with a game being considered good or bad. But it's not a perfect correlation. Simon Belmont in Castlevania was not very expressive. But it was the avatar's carefully considered limitations which helped fill the game with tension and balance the difficulty. Imagine if Simon could run, jump and smash like Mario from Super Mario Bros.! The game would be a cakewalk and the atmosphere would be ruined.

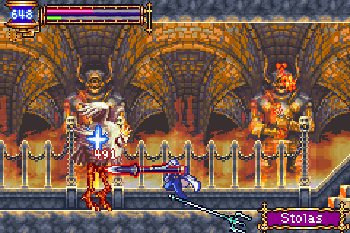

Later, when the Castelvania series was rebooted with Symphony of the Night, one of the most radical changes to the game was not the Metroid-style open world, but the expressiveness of Alucard as an avatar. It transformed the game-play and enabled a kind of fast-paced, aggressive play style that simply couldn't have existed in the 8-bit games. It made sense at the time, the son of Dracula, should be able to move so quickly, so fluidly, so much like you wanted him to play.

So it's important not to think of this term as being on the same axis as "good" and "bad", but just another dimension to consider when describing a game character and the play styles that character might be capable of.

Consider Leonardo in the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles arcade game. Not too terribly expressive: you can walk, jump, and strike from walking or jumping, but the rest of the game presentation more than makes up for any limitations of your character. TMNT is widely considered to be a great game.

Now consider Frank Castle in The Punisher Arcade Game. He can walk, run, slide kick, stand and fight, shoot, throw, jump and throw, jump kick, pick up weapons, shoot, toss grenades and more. He's a wildly expressive character, yet the game is not well known. Arguably the art direction, sound and overall game design of TMNT is better. But The Punisher is still a great game. (full disclosure, I like The Punisher game more).

Expressive character is a term I'd like to use from now on, and you can think of this post as a placeholder, a reference point to explain what it means. I invite other reviewers to refer to this concept when describing games, it gives us digital sommeliers a common reference point and expands our meaning.

Unlike how a Sommelier might call upon a rich descriptive lexicon to describe a wine, game reviewers have long struggled (and needed) to develop a vocabulary to describe a game to those who have not experienced it - to draw not just a visual picture with words, but an experiential image. A game might have "tight controls" or "loose controls" for example, with "tight" being perceptually better in most cases.

Unlike how a Sommelier might call upon a rich descriptive lexicon to describe a wine, game reviewers have long struggled (and needed) to develop a vocabulary to describe a game to those who have not experienced it - to draw not just a visual picture with words, but an experiential image. A game might have "tight controls" or "loose controls" for example, with "tight" being perceptually better in most cases.Since the beginning. most games have been built around the idea of controlling an on-screen character or avatar. Derived from board game pieces, the game designers attempt to put your avatar into a variety of situations, relying on your shared identity and your instincts for self-preservation to spur you into action. During gameplay, you might be controlling a better-than-you-are Mario, capable of jumping, hopping, ducking, sliding, smashing, bouncing, stomping and otherwise careening about the play field in a dynamic controlled chaos - often using verbed moves in combination. Or you might be in charge of Duke Togo, capable of a saunter, a single height jump, and shooting while standing -- and that's it.

Putting on digital Mario, inhabiting him, you feel empowered, like you can do anything. As the game presents new situations, you feel like you have a toolbox of responses you can use to deal with them. Two different players might even approach the same part of the game with completely different approaches.

Poor Duke, however, feels like walking around a city wearing a refrigerator box while trying to maintain balance on a pogo stick. You feel panic at almost every encounter because your options are so limited: jump in mad desperation or stand there and absorb bullets until one of your wild shots finds a bad guy.

Mario allows you to express yourself, Duke doesn't. The game forces you to inhabit a hopelessly outclassed character, while Mario can be virtuosically played in any number of ways. Mario is an expressive character - and it's this expressiveness that defines the entire series to this day.

It's funny how often the presence of such an avatar can correlate with a game being considered good or bad. But it's not a perfect correlation. Simon Belmont in Castlevania was not very expressive. But it was the avatar's carefully considered limitations which helped fill the game with tension and balance the difficulty. Imagine if Simon could run, jump and smash like Mario from Super Mario Bros.! The game would be a cakewalk and the atmosphere would be ruined.

Later, when the Castelvania series was rebooted with Symphony of the Night, one of the most radical changes to the game was not the Metroid-style open world, but the expressiveness of Alucard as an avatar. It transformed the game-play and enabled a kind of fast-paced, aggressive play style that simply couldn't have existed in the 8-bit games. It made sense at the time, the son of Dracula, should be able to move so quickly, so fluidly, so much like you wanted him to play.

Consider Leonardo in the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles arcade game. Not too terribly expressive: you can walk, jump, and strike from walking or jumping, but the rest of the game presentation more than makes up for any limitations of your character. TMNT is widely considered to be a great game.

Now consider Frank Castle in The Punisher Arcade Game. He can walk, run, slide kick, stand and fight, shoot, throw, jump and throw, jump kick, pick up weapons, shoot, toss grenades and more. He's a wildly expressive character, yet the game is not well known. Arguably the art direction, sound and overall game design of TMNT is better. But The Punisher is still a great game. (full disclosure, I like The Punisher game more).

Expressive character is a term I'd like to use from now on, and you can think of this post as a placeholder, a reference point to explain what it means. I invite other reviewers to refer to this concept when describing games, it gives us digital sommeliers a common reference point and expands our meaning.

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

The Dreadnaught Factor - Atari 5200

The night before Christmas my cousins and I built a fortress of presents under our fake Christmas tree and lay under the plastic needles looking up at the whirl of blinking colored lights and tinsel. Protected by our formidable barrier of merriment, no adults dared come into the family room. Thus isolated, we were free to try and discern what gifts we would be getting that year. One huge box with my name on it had me transfixed all evening. The anticipation had grown so strong that our parents, unable to get us to bed, had allowed us each to open two presents.

The first was that box of mysteries, which turned out to be an Atari 5200. My second present (opened at my Grandmother's subtle hint) was The Dreadnaught Factor. This negotiated arrangement concluded, our parents finally got us into some kind of horizontal laying position, in sleeping bags under the tree in the remains of our assaulted holiday stronghold. Sleep escaped us and by two in the morning we had figured out how to hook the Atari up to the family television and we started to play until exhaustion and hunger wiped us out late the next evening.

Before the 5200 our combined video game playing experience consisted of time playing arcade games, my neighbor's Atari VCS/2600 and some home computer games on some of the various 8-bits of the time. Nothing we had experienced to that point prepared us for this game.

Star Wars still hung huge in the public consciousness, but the arcade had failed to provide an interactive experience as cinematic, as awesome as the movies (the arcade Star Wars hadn't yet been released). The closest experience by Christmas 1982 was probably Parker Bothers' Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (SW:TESB) for the Atari VCS/2600 which tried to replicate the Battle of Hoth.

To me, TDF will always be the 5200 port first and foremost. It will always evoke that early morning, hooking up my new Atari to the TV, shushing each other and turning the TV down so we didn't wake anybody up. The mushy feel of the 5200 rubber buttons and the collar on the joystick, and the feeling of frustration at each loss and hitting the green "START" button over and over and over again.

To me, TDF will always be the 5200 port first and foremost. It will always evoke that early morning, hooking up my new Atari to the TV, shushing each other and turning the TV down so we didn't wake anybody up. The mushy feel of the 5200 rubber buttons and the collar on the joystick, and the feeling of frustration at each loss and hitting the green "START" button over and over and over again.

The first was that box of mysteries, which turned out to be an Atari 5200. My second present (opened at my Grandmother's subtle hint) was The Dreadnaught Factor. This negotiated arrangement concluded, our parents finally got us into some kind of horizontal laying position, in sleeping bags under the tree in the remains of our assaulted holiday stronghold. Sleep escaped us and by two in the morning we had figured out how to hook the Atari up to the family television and we started to play until exhaustion and hunger wiped us out late the next evening.

Before the 5200 our combined video game playing experience consisted of time playing arcade games, my neighbor's Atari VCS/2600 and some home computer games on some of the various 8-bits of the time. Nothing we had experienced to that point prepared us for this game.

Star Wars still hung huge in the public consciousness, but the arcade had failed to provide an interactive experience as cinematic, as awesome as the movies (the arcade Star Wars hadn't yet been released). The closest experience by Christmas 1982 was probably Parker Bothers' Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (SW:TESB) for the Atari VCS/2600 which tried to replicate the Battle of Hoth.

SW:TESB blew my child-like mind when I first played it at a friend's house. The battle it recreates is one of the most iconic scenes in movie history. But the game ultimately disappointed me when I couldn't grapple and trip the legs of an AT-AT and the rest of the gameplay just turned into a competition of how many times I could hit the fire button while zooming left and right. There simply wasn't much there there, even young me caught onto that.

It's hard to trace back the history of the idea of a "Boss Rush" in video games, but SW:TESB might be close to the origins though the term hadn't been coined yet. You really only ever fight what we'd think of today as bosses, AT-ATs.

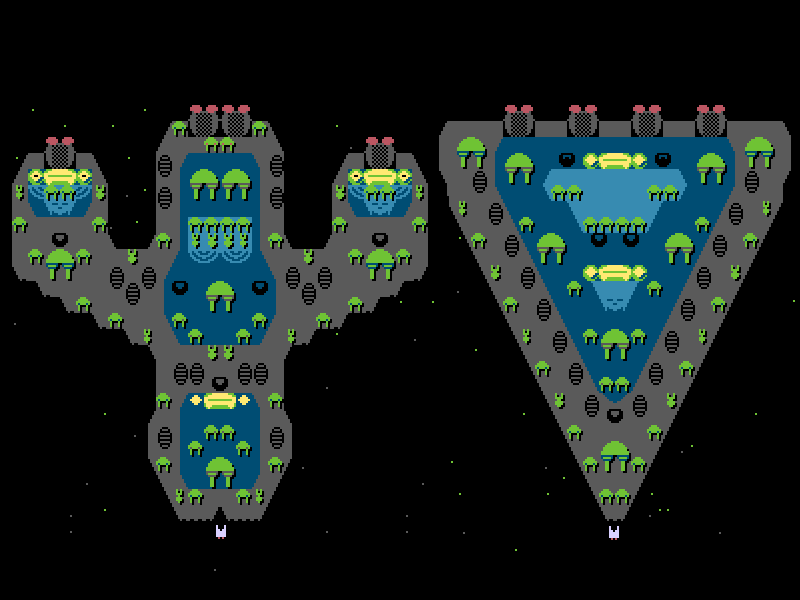

In this Star Wars environment, The Dreadnaught Factor (TDF) took a different spin on the idea. Instead of a horizontal shooter, TDF on the Atari 5200 is a vertical shmup (the port for the Intellivision is basically the same game in a horizontal format) built entirely around the boss rush.

Just like other contemporary vertical shmups, you pilot a lone fighter craft. Unlike all those shmups however, you never really fight other enemy fighters, you fight huge multi-screen spanning Star Wars Star Destroyer like "Dreadnaughts".

In 1983 this was unbelievably innovative as a game, unbelievably derivative of Star Wars, and freaking awesome. It probably wasn't until Shadow of the Colossus on the PS2, 22 years later, that a similarly cinematic David and Goliath game set you up with odds so tilted against your favor.

TDF does some things amazingly well, full-screen multi-directional scrolling (something the NES struggled with early on), tons of targets, a countdown clock that built up tension as the game progressed and more.

You strafe a giant dreadnaught, picking off cannons, missile launchers, engines and other targets -- and this is important, the damage you do to the dreadnaught is real. You take out the engines, it slows its descent towards Earth, you take out the bridge and it's limited in how it can coordinate defensive fire. These aren't just symbolic target points. You measurably impact and frustrate the enemy's ability to attack. The goal, borrowed again from Star Wars, is to plug up all the vents on the surface of the ship by bombing them, causing the ship's power system to overload and blow up.

In structure it's also a bit of a riff on the 1980's Missile Command. In Missile Command your view is on the entire battlefield and the contact between your defense missiles and the in-bound enemy ICBMs is abstract. In TDF, you are the missile in essence. The feeling of being overwhelmed and under attack is still there. Where Missile Command is a strategic game, TDF is purely tactical. You don't just send up a defense and pray to the fates for salvation. You are the direct instrument, the tip of the spear between the invaders and oblivion.

To cement the Star Wars influence, the first dreadnaught you encounter is about as close of a carbon copy to a Star Destroyer as could reasonably be rendered in 8 glorious bits. The triangular shape instantly recalls those unstoppable flexions of emperial power and cues you into what you're supposed to do, fight it! If the Rebels could do it, you can!

TDF runs with the idea and you start fighting ships of all kinds of layouts. And of course they get more and more aggressive as you go, guns fire more often and more accurately, missiles launch more quickly, etc. Before you launch each fighter, you get a proximity view that lets you know how close the dreadnaught of the level is to firing range to the Earth. The Earth rotates slowly down at the bottom of the screen in a surprisingly sophisticated graphical effect for the early 80's. As you move up the levels, the number of dreadnaughts you have to defeat to pass a level increases, eventually reaching huge armadas you need to beat.

Despite the screen filling cinematic experience, TDF is a strangely quiet game. There's no music, and just a handful of sound effects. The effects that are there are satisfyingly arcadey. I know the 5200 was limited audio-wise, but I still think it suffers a bit from this in presentation.

Control with the original 5200 controller is superb, when the 5200 controller works, it's actually a good stick for the era -- it's just too bad the build quality on the innards was so poor. The ship control is precise and you can move to where you need to make your approach. Under emulation it's also great, but there's something lost on a digital d-pad. If your emulator supports it, going at it with an analog thumb stick is a close experience.

There's a surprising amount of tactical strategy here, do you go for the engines, but risk getting shot by the anti-aircraft fire? Or should you go directly for the vents, but risk the ship making it to the Earth? Maybe you decide to go for a suicide run, but risk running out of your limited supply of defense fighters. As the ships change shape and armament, your attack strategy can radically change.

If you come into this game from a modern context you might be a little disappointed. It's really just you and a handful of ships against this overwhelming enemy. There's no powerups (already old hat by this time courtesy of 1981's Galaga), but the gameplay feels so modern that you're going to assume there is. The enemy ships, while they also change in configuration and aggressiveness, don't get new weapons or goals. You basically see all of the enemy's tech tree and armament on your first strafing pass.

A modern game would have kept you and the dreadnaughts progressing in power until you were a virtual unstoppable death dealer and the dreadnaughts were unbeatable shards of pure might. But this is a classic game, and it's a miracle a game fit at all in the handful of kilobytes it was budgeted. However, in all the good ways that F-Zero is a pure racing game, TDF is a pure boss-rush shmup. It's almost like a more modern, casual indie game in this way.

TDF is kind of a forgotten gem. It wasn't an Arcade port, and the 5200 died a quick death. There's a port for Atari 8-bit computers that's basically the same as the 5200 (the 5200 was pretty much just a console-ized version of the computers), but the Atari 8-bit computers weren't nearly as popular as some of the other computers of the era. And there's the aforementioned Intellivision port which seems to be fairly well known inside of the Intellivision community, which is pretty much a horizontal remake of the game, but I've never really favored that take on the concept.

Still, for people that remember it, it seems to be almost universally loved. There are hacks of the game to give you more ships to fend off, and remakes. Modern reviews for it are strong.

To me, TDF will always be the 5200 port first and foremost. It will always evoke that early morning, hooking up my new Atari to the TV, shushing each other and turning the TV down so we didn't wake anybody up. The mushy feel of the 5200 rubber buttons and the collar on the joystick, and the feeling of frustration at each loss and hitting the green "START" button over and over and over again.

To me, TDF will always be the 5200 port first and foremost. It will always evoke that early morning, hooking up my new Atari to the TV, shushing each other and turning the TV down so we didn't wake anybody up. The mushy feel of the 5200 rubber buttons and the collar on the joystick, and the feeling of frustration at each loss and hitting the green "START" button over and over and over again.Tuesday, August 12, 2014

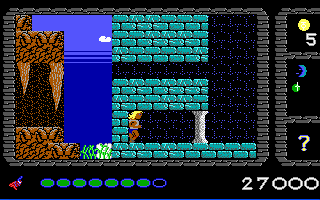

Dark Ages - MS-DOS

When you're dealing with a platform as old as the PC you see lots of halting transitions. Text-to-monochrome graphics, monochrome graphics to 4-color CGA, 4-colors to 16 and so on. Unlike game platforms, the PC platform is in a constant state of flux. Lots of gradual in-generation upgrades punctuated by massive, but uneven jumps in capability -- all at vast expense compared to consoles.

Audio hardware was no exception to this. It's hard to imagine today where every computer has built in highly capable audio hardware, but there used to be a vibrant and highly competitive market for add-on audio cards for home computers. One of the very earliest of these add-on cards was produced by a Canadian company, Ad Lib, Inc makers of a YM3812 powered FM audio card.

Originally built into the hardware chasis, the PC Speaker was basically designed to produce single tone error code beeps when the video hardware had a problem. Considered more reliable than most of the other early PC hardware, the Speaker was initialized first and would give a coded number of beeps depending on which piece of primitive hardware was going to cost you a small fortune because it died.

Later programmers learned to change the tone and play simple beeps during productivity operation, or simple single voice songs. Even later programmers learned to make more complicated sound effects (and even play back very scratchy digitized audio). But the hardware was horribly crippled and this was recognized pretty early. You can get an example of what playing an early PC game was like here:

What about AdLib? Well, a competing company, Creative Labs, produced the now legendary Sound Blaster which was basically an AdLib clone but also included digital audio features. Thousands of PC games feature AdLib compatible music with digital sound effects, like Doom. This kind of tiny, FM music was the mainstay of almost all PC games until the CD-ROM became affordable and popular. It was clear that the PC Speaker was not going to be part of future gaming. But neither was AdLib the company. Competition was just too great and gamers didn't buy their follow on hardware. The company went bankrupt not a year after Dark Ages came out. Yet the Creative Labs Sound Blaster family carried on the Ad Lib name for many years.

Replogle learned lots of lessons from this game. His next game was the original Duke Nukem platformer, which of course launched the now infamous Duke Nukem franchise. He followed this with the joyful Cosmo's Cosmic Adventure, a fitting CK-like platformer. Another Duke platformer and finally Duke Nukem 3D.

Audio hardware was no exception to this. It's hard to imagine today where every computer has built in highly capable audio hardware, but there used to be a vibrant and highly competitive market for add-on audio cards for home computers. One of the very earliest of these add-on cards was produced by a Canadian company, Ad Lib, Inc makers of a YM3812 powered FM audio card.

Originally built into the hardware chasis, the PC Speaker was basically designed to produce single tone error code beeps when the video hardware had a problem. Considered more reliable than most of the other early PC hardware, the Speaker was initialized first and would give a coded number of beeps depending on which piece of primitive hardware was going to cost you a small fortune because it died.

Later programmers learned to change the tone and play simple beeps during productivity operation, or simple single voice songs. Even later programmers learned to make more complicated sound effects (and even play back very scratchy digitized audio). But the hardware was horribly crippled and this was recognized pretty early. You can get an example of what playing an early PC game was like here:

While the graphics capability had improved a bit by 1991. The audio hadn't really changed much. By the late 1980s, Roland had stepped in to sell it's MT-32 MIDI synth hardware for PCs. It sounded (and still does) sound amazing - a quantum leap in PC audio. But at somewhere between $500-1000, with limited audio support outside of Sierra On-Line, was simply not an option for most PC owners.

Enter Ad Lib, Inc. A small Quebec company started by a former music professor named Martin Prevel, Ad Lib produced a simple, relatively cheap add in card. It didn't sound even close to as high quality of the MT-32, but by 1988 PC users were dying for just about anything better than the beeps and boops they were used to. Being inexpensive, it found a lot of buyers relatively quickly, and in the commercial games market embraced it with quite a few "AdLib Compatible" games (with Sierra's 1988 Kings Quest IV being the first game to support it). However, the shareware and freeware market lagged considerably.

Founded the same year as Ad Lib, Inc., Apogee Software Ltd., was one of the first companies to make a serious commercial effort at the shareware model. They introduced a novel "Apogee" model for game publishing: give the first 1/3rd of the game away for free and sell the 2nd and final chapters of the game. Some of the biggest games in history came out of this model: Doom, Quake, Duke Nukem 3D. But before those games even had a line of code written, an entire library of great PC games were put out under this model by many talented game makers.

Todd Replogle was one of these game makers. He had designed a couple games that were published by Apogee -- each one making a significant graphical leap over the last. His first game, Caves of Thor, used glorified text characters to represent an adventure game (not too unlike today's Dwarf Fortress in appearance). His next jumped to 4-color CGA graphics. By 1991 he was working on his next great leap. Except this time it was to have two major leaps, 16-color graphics and Ad Lib music - a first in the shareware industry. The result was the Dark Ages trilogy.

While there had been plenty of 16-color games by 1991, there were still relatively few platformer games a la Super Mario Brothers. but one of those had been the wildly successful Commander Keen series, also published by Apogee and made by none other than John Carmack and John Romero of Doom and Quake fame. Apogee was ready for more. Carmack and Romero had taken Keen to be published by Softdisk so that left them without another major platformer. Replogle took on the task, along with Allen H. Blum III as artist and Keith Schuler as the composer.

So is Dark Ages a worthy follow up to Commander Keen (CK)? No is the simple answer, but the real answer is more complicated than that. Dark Ages showed that small software houses could technically do all the fancy hardware stuff the big boys like Sierra were doing. However, the execution is fantastically uneven.

Gameplay-wise, it's obvious that the Replogle was going for a Shadow of the Beast (SotB) style game. It's not a Mario-like exploration fest. You run left-to-right and shoot some kind of projectile at the various enemies you come across. There's not many jump puzzles or really much else to the game. You basically do your best to emulate an unstoppable juggernaut until you reach the end of the game. It's not poorly done at all, it's a solid play, but it's a less expressive game than CK or SotB.

However, level design is surprisingly thoughtful, requiring a good understanding of how the character moves and really being built around the character and what he can and cannot do -- in much the same way Castlevania is built around Simon Belmont's movement abilities. There's woefully few enemy types. But the game uses them in clever combination to keep your progression relatively interesting and challenging.

The graphics are not great. Despite having a dedicated artist. Characters lack personality or design, are poorly animated and lack the kind of polish you'd expect from a platform game on any platform by 1991. And it's probably this that really put this game in the bin of forgotten games. After a long play, the graphics start to feel impossibly jerky and constrained. It's as if you're playing a color upgraded Tiger LCD game and not a proper video game. There's lots of level variety, and each area feels different enough. But it's not enough to overcome these issues.

Audio is a fascinating example of a transition point in technology. The music is great, better than most games' use of the AdLib synth. Keith Schuler really tried to give each area a different feel, but provide thematically coherent music to the theme of the game. It pumps along and masks lots of the issues with the graphics. I personally kept playing just because I was enjoying running along killing bad guys to this music. It surprisingly holds up well.

Sound effects though do not use the AdLib card. I'm not sure why exactly, but it wasn't uncommon in the era. Perhaps programmer limitations, or development efficiency (since playing the game sans AdLib meant just not playing the music), it's still puzzling. While later games provided passable sound effects via the PC Speaker, in Dark Ages it's also slightly annoying. The main sound effect you hear as the near constant sound of your projectiles, playing the same few notes thousands upon thousands of times while you work your way through the game. And unlike whatever speakers you have plugged into your AdLib, the PC Speaker traditionally doesn't have any volume control. It's just on. Replogle of course, knew that the sound effects weren't great.

So where does this leave the Dark Ages trilogy? Should you ignore it or play it? I'm just on this side of playing it. I think it's a more important game than it gets credit for. After this game, it was no longer really acceptable to publish games without at least AdLib music. It's really a pivotal point in the PC games industry. It's the very beginning of the path of shedding careful observance of the traditional hardware you computer just happened to come with, and the start of people really customizing their computers. This trend would help kickstart the 3d graphics card revolution which we're still in the midst of today.Peter Bridger: It's June 1991, Apogee have just released Duke Nukem (the original side scroller), the sound effects made by Scott Miller. Should he write some PC speaker sounds effects for DNF?Replogle: HAHAHA! Speaker sound effects are only appropriate with computers lacking digital sound capabilities, something uncommon in all but the oldest tabletop PCs and laptops.

What about AdLib? Well, a competing company, Creative Labs, produced the now legendary Sound Blaster which was basically an AdLib clone but also included digital audio features. Thousands of PC games feature AdLib compatible music with digital sound effects, like Doom. This kind of tiny, FM music was the mainstay of almost all PC games until the CD-ROM became affordable and popular. It was clear that the PC Speaker was not going to be part of future gaming. But neither was AdLib the company. Competition was just too great and gamers didn't buy their follow on hardware. The company went bankrupt not a year after Dark Ages came out. Yet the Creative Labs Sound Blaster family carried on the Ad Lib name for many years.

Replogle learned lots of lessons from this game. His next game was the original Duke Nukem platformer, which of course launched the now infamous Duke Nukem franchise. He followed this with the joyful Cosmo's Cosmic Adventure, a fitting CK-like platformer. Another Duke platformer and finally Duke Nukem 3D.

Saturday, July 5, 2014

Castlevania: Aria of Sorrow/Castlevania: Akatsuki no Minuet (キャッスルヴァニア ~暁月の円舞曲)

The Castlevania II: Simon's Quest (C2SQ) release on the Nintendo Entertainment System, part of the 1987 onslaught of sequels-that-went-entirely-different-directions, was part of a concerted effort to make games more "epic" in scale. In video games, nothing was more epic than the RPG, offering dozens of hours of playtime, experience points, levels, upgrades, dialog and otherwise all the things that were missing from the 45 minute arcade games that had inspired consoles up to that point. Japanese game designers had long attempted to use the RPG model as a way of breathing more life and playtime into an otherwise short game. A number of improbable games with "RPG Elements" came out as part of this experiment in fusing styles, racing games, sports games, even a pinball game. C2SQ was one of these many, sometimes confused, products that emerged.

Whether C2SQ is a good game or not is up to some debate. The longer view of history has not treated it universally kind. It's plagued by dubious design decisions, weak powerups, loads of grinding, unknowable puzzles and backtracking, instant deaths and other annoyances. But it was a noble attempt, and everybody I knew had a copy of it, and thought it was awesome at the time even if none of us ever finished it. The next 11 Castlevania games were a return to a decidedly non-RPG style of game.

By the mid-90s it was clear that the Castlevania jump-n-whip model had run its course, yet it was still a vibrant and beloved franchise. One of the chief designers of the Castlevania, Koji Igarashi, lamented seeing piles of Castlevania games in the bargain bin at local stores -- the games were popular, but short-lived. Furthermore, consoles had moved on and the 3d revolution was in full-swing, yet Castlevania's signature gameplay mechanics didn't translate well to 3d.

A contemporary of the original Castlevania game on the NES was Metroid. Metroid was a revolutionary game. Using the limited hardware available at the time, Gunpei Yokoi (known for his unique philosophy of "Lateral Thinking of Withered Technology") defined an action-adventure-exploration model for games. Instead of slavishly hammering in bits of commonplace RPGs into other game genres, Metroid eschewed most of these things. The goal was exploration and the reward for exploring was power ups. This was copied in later games like Blaster Master, but the Metroid games continues to stand as a gold-standard for this kind of game.

This model, and the RPG-like C2SQ formed the kernel then for the revitalization of the Castlevania Franchise. In 1997 we saw the release of one of the finest video games of all time, Castlevania:Symphony of the Night (CSOTN) It was a powerful homage to Metroid, yet refined the game style on almost every level. More a 32-bit version of the what the Metroid formula had become with Super Metroid, so good was it that the term "Metroidvania" was coined to capture this particular genre of game. The games played so close to each other that you could almost swap the tilesets of each game and not know it.

Still, despite rave reviews, Konami tried to put out various 3d-style Castlevania games to almost universally limited success. By 2001 it was clear the Castlevania didn't have legs as a 3d game. It was this year that Nintendo was going to release the Game Boy Advance and there was no doubt that a Metroid game was going to follow. Inspired yet again, Konami decided to reach back into their archive of past successes and remembered CSOTN. Deciding to release a Castlevania game as a GBA launch title, Konami pulled out all the stops and released Castlevania: Circle of the Moon, the first Metroidvania style Castlevania in almost 5 years.

It was so successful that it spawned 2 more immediate sequels: Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance and Castlevania: Aria of Sorrow (CAoS) all on the GBA. Typical of immediate sequels, Harmony of Dissonance was less successful, but Aria of Sorrow nails the formula.

This mechanic also replaces the traditional Castlevania optional weapon. You can get everything from a spear throwing ability to a giant skeleton arm that follows you around smashing enemies to bits. One of my favorites is a Sith Lord style lightning charge. The combination of souls, and other weapons you pick up throughout the game provide you with nearly endless combinations of attack powers and it's worth playing through the game a few times to see what souls and weapons you'll end up with.

As you continue to power up, you eventually become a virtually unstoppable juggernaut. There are some who complain about this, but I never felt upset about it, it keeps the late game breezy as you flitter around the castle chasing down that one last item, or adding that one last secret room your couldn't get to before to your map.

There's also an unbelievable number of primary weapons, with wildly different properties. It's fun to find them and then try some of the oddball ones out for a while. Some of the weapons look great on paper, but don't work well in certain combat situations, so you'll find yourself learning the feel of each weapon and quickly switching between different ones even during the course of a single fight. This keeps combat brisk and interesting for most of the game.

The game plays really well, controls are tight and a handy backdash move can turn some early-to-mid game fights into mini fencing duels with some of the stronger enemies. Your character evolves and stays expressive throughout the game. There really aren't too many cheap hits, and to be honest the game isn't really all that hard. There are plentiful save points throughout the castle and the automap does a reasonable job of showing where you need to explore next. There's a few maze-like sections that can get tedious to figure out, but they're more than balanced out by the rest of the game.

Graphics are pretty good. They don't suffer from the typical GBA "developed at a higher resolution then scaled down to the GBA resolution" problem that a great many GBA games have. It's clear that Konami, like Nintendo, developed this game from the get-go to fit within the limitations of the system, and the presentation of nearly everything in the game is fantastic (your main character's funny looking long legged running cycle notwithstanding).

The Castlevania series is legendary for the amazing music. Even on the lowly Black and White original Gameboy, the music was stunning. CAoS's music is lackluster by Castlevania standards, great by normal GBA standards. It's more than competent and rarely intrudes, but it's not memorable in the "catchy" sort of way you'd like. Is it bad? No, definitely not, it's actually quite decent, just not up the kind of standard you'd expect out of the series.

But wait, there's more. The game has different endings and even an entire second quest where you play through the game as a Belmont, whip and all. It's not as fleshed out as the main game, but Julius Belmont plays different enough from Soma that it's worth puttering around the castle for a couple hours to see how to solve different situations. It's fun and keeps the game replayability high, long after you've exhausted the normal quest.

It's obvious that CAoS did something right, while no more Castlevania games graced the GBA, the series kept on strongly, with no less than three similarly styled Metroidvanias coming out on the Nintendo DS through 2008. That makes a total of 7 games of the Metroidvania type across 3 platforms (with some coming out on the WiiU Virtual Console) -- and to be honest it doesn't really matter which ones came out when and on which platform, they're all only moderately different, and to be honest, the Castlevania story doesn't matter at all, any or each will give you hours of enjoyment. They're all just more of the same awesome game style.

Understandably, Konami decided to abandon the Metroidvania formula after all those similar games. At this point, Castlevania is well down the road of becoming a moderately good God of War clone. If we're to see more games of this type, they'll probably not be coming out of Konami.

Wednesday, May 21, 2014

Astro Boy: Omega Factor/Astro Boy: Tetsuwan Atom (アストロボーイ・鉄腕アトム) - Game Boy Advance

Coming of age in wartime Japan, Osamu Tezuka found himself pulled from middle-school and pressed into service at an imperial arsenal. Standing lookout for American bombers in a watch tower, he survived a series of ferocious firebombings of his hometown, Osaka. He eventually went back to school and graduated with an M.D., but the memories of the bombings and his feelings on war and conflict never left him.

He decided not to practice medicine and instead chose to give voice to his feelings through his true love, cartoons. Prolific is too small a word to use to describe his artistic output. With a body of work of more than 150,000 pages in hundreds of volumes he virtually defined the medium of manga in Japan for decades - with luminaries as well known as Hayao Miyazaki referring to Tezuka as a major influence.

He decided not to practice medicine and instead chose to give voice to his feelings through his true love, cartoons. Prolific is too small a word to use to describe his artistic output. With a body of work of more than 150,000 pages in hundreds of volumes he virtually defined the medium of manga in Japan for decades - with luminaries as well known as Hayao Miyazaki referring to Tezuka as a major influence.

Unlike other post-war cartoonists who sought to rectify feelings of loss and victimization at the hands of foreign aggressors, Tezuka often filled his works with themes of post-racial, post-national reconciliation and peace. One of this most globally regarded works is Astro Boy.

Ending print run in the late 60s, Astro Boy of course saw recreation as an anime series in the 1980s. Timed to hit at the same time as a new 2003 series, Astro Boy: The Omega Factor (AB:TOF) is a Game Boy Advance side-scrolling brawler with silky controls and a great sense of style that stays mostly true to the spirit of the original manga that has a few flaws that keep it from greatness.

Made by the legendary Treasure and Hitmaker (Sega AM3), AB:TOF is a bright and breezy game with lots of visual impact that shows off lots of what the GBA could do in the right hands. It features tons of recognizable Astro Boy characters, rendered in loving detail and a surprisingly long and possibly overly ambitious game for a portable experience.

While many reviews compare AB:TOF to the Mega Man series, I think this unnecessarily conflates two cute robot fighters for justice. There's really very little in common between the games. AB:TOF is also often called "action platformer", but there's very little platforming in the game in any traditional sense. Instead you're put in charge of a cute fighting mechanoid who jumps and flies around the screen with ease to punch and kick and laser and machine gun your enemies. Combos flow freely and special moves are wonderfully easy to pull off without any of complex Street Fighter/Tekken finger twisters. It's fun to pound your enemies and send them careening across the screen into each other. That fun factor kept me playing long after I had any reason to. In, fact I ended up playing through the entire game about 4 times I was having such a kick with the fluid controls.

In typical Treasure style, the game is loaded with bosses, sometimes bosses after bosses after bosses. In the context of a brawler this actually works pretty well and really turns the game into a boss rush game with filler levels full of fairly easy look-alike enemies. Not all the bosses are great, but the ones that are good are interesting and screen filling.

To mix things up there are also shooter levels. Astro Boy flies, Superman style, and fires a laser out of his finger. A variant of the shooter levels, Astro Boy assumes a vertical, slower, position, but can fire in both directions. These are pretty welcome diversions from the brawling and offer some surprising variety to the game. They aren't Gradius, but they're effective for what they do.

The music is upbeat, catchy and perfectly fits the game. I don't think I would make a big effort to listen to any of it outside of the context of the game, but it's actually kind of hard to think about AB:TOF without the great music. It perfectly complements the on screen action in almost every part of the game. I think the only place the music really suffers is the lousy sound production of the GBA (at least as compared to the SNES's glorious Sony produced SPC700).

So what keeps this game from greatness? In a word, polish. It feels like the developers set a scope far too ambitious for the development resources available -- the game was in serious need of some critical editing. By combining story lines from many of the manga issues they resulted in a huge, virtually unfollowable story involving time travel, international politics, doomsday machines, tragic loss, ancient lost civilizations and more, with far too much dialog for a brawler. It's too much, and it's not tied together. The late game suffers as well as it tries to accommodate this mess.

After the first few overly long bits of talking, you'll find yourself just skipping through them. But of course this is a mistake as clues are embedded in the conversation that helps you solve the time-travel riddle the conclusion of the game hangs off of. You can get pretty far in the game ignoring this nonsense and have a more enjoyable time, even if the trade-off is that you probably won't be able to complete the game, destined to endless loop through time not knowing about the central conceit in the game.

After the first few overly long bits of talking, you'll find yourself just skipping through them. But of course this is a mistake as clues are embedded in the conversation that helps you solve the time-travel riddle the conclusion of the game hangs off of. You can get pretty far in the game ignoring this nonsense and have a more enjoyable time, even if the trade-off is that you probably won't be able to complete the game, destined to endless loop through time not knowing about the central conceit in the game.

The biggest problem I felt while playing was the feeling of sameness throughout the game, despite all the attempts at variety. I think this stems from the way the game sets up the fights: you'll run a bit, the screen will lock into a small "arena" and a wave of the same enemy will drop down out of the sky. You'll destroy all of the enemies then move on to the next "arena" and fight a slight variation of the enemy you just fought in the previous arena -- a different color, or maybe a different size. And you'll do this for a dozen times in a level, maybe broken up by a couple waves of a different enemy. In most brawlers, you might fight one kind of enemy, then another, then some combination of the two to make it interesting. AB:TOF is almost completely devoid of these combination battles and I think the non-boss portions of the game really suffers for it as non-boss fights start to drag on and on.

Another problem is the surprising amount of slowdown in the game. I can't ever really recall playing a GBA game with slowdown, but there are a number of moments with only 3 or 4 sprites on the screen at once and the frame rate drops terribly. It's weird, especially given Treasure's renown for manic gameplay with screens piled full of enemies. It feels like an optimization issue that would have been solved late in a normal development cycle. It might also be the reason for the lack of combination battles I talk about above.

Finally, the late game suffers from a really pointless time-travel puzzle based on obscure clues referencing one of a few dozen characters you might have met once in the game for a few lines of dialog. It's really not worth figuring out on your own because it'll involve a careful reading of miles of hard to follow dialog. If you want to see the game ending, it's best to just look up the solution someplace and follow it.

I think if the game had gone through a tight editing round early in development the game wouldn't have overreached so much and a bit more polish could have solved some of the issues in the game. It could have turned this from an okay B game into an A game. There's really lots to love here, so don't let these issues turn you off from the game -- it's a fun game that's totally worth a play through. Just don't get hung up on the story.

Sunday, March 16, 2014

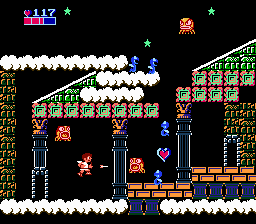

Kid Icarus/Hikari Shinwa: Parutena no Kagami (光神話 パルテナの鏡) (Myth of Light: The Mirror of Palutena) - Famicom/NES

Many years ago, when Nintendo was still building out franchises, and before backgrounds became common things in NES games, they produced a reusable game engine. In the mid-80s (especially mid-80s Japan which still struggles with modern software practices to this day) this was pretty mind-blowing. This engine was used in two games, one of the two games, Metroid, has become the stuff of legends even spawning it's own game genre name. The other, Kid Icarus is no less loved, but has always sat in the shadows of it's big brother.

Growing up, I was aware of Kid Icarus (KI), but fighting space aliens was so much more relevant to young me than Greek legends. I remember playing it one time on a game kiosk and feeling very non-plussed about it. I was surprised to learn, years alter, that the same designer and engine were used in both games. When sitting down to review it, I really wanted to analyze why that was, and why I couldn't find the love for this game that I know many others have and why did I love Metroid but hate KI? It turns out these were the wrong questions. KI is an amazing game, and my feelings were based on just the purely superficial first impressions I had as a kid.

Growing up, I was aware of Kid Icarus (KI), but fighting space aliens was so much more relevant to young me than Greek legends. I remember playing it one time on a game kiosk and feeling very non-plussed about it. I was surprised to learn, years alter, that the same designer and engine were used in both games. When sitting down to review it, I really wanted to analyze why that was, and why I couldn't find the love for this game that I know many others have and why did I love Metroid but hate KI? It turns out these were the wrong questions. KI is an amazing game, and my feelings were based on just the purely superficial first impressions I had as a kid. However, the first impressions of the game are hard to get past. Like Metroid, you start severely underpowered. But I feel like Metroid starts the player up the learning curve more gently. Metroid uses all kinds of small hints to train the player about the world. You try to run right, you can't. So it forces you to run left where you find your first power-up. You start with a couple weak enemies in unthreatening placements so you can practice aiming and learning that you can fire up as well as horizontal. All these things clue you in to how the game world, for the rest of the game, is going to work.

However, the first impressions of the game are hard to get past. Like Metroid, you start severely underpowered. But I feel like Metroid starts the player up the learning curve more gently. Metroid uses all kinds of small hints to train the player about the world. You try to run right, you can't. So it forces you to run left where you find your first power-up. You start with a couple weak enemies in unthreatening placements so you can practice aiming and learning that you can fire up as well as horizontal. All these things clue you in to how the game world, for the rest of the game, is going to work.

Kid Icarus, doesn't really do any of these things. You start weak, and enemies are thrown at you from the beginning. You collect hearts, but they don't restore your life, and you climb climb climb perpetually up. There are doors, but the first few you find don't really help you. The difficulty is relentless. My first couple plays, I died so early and so often I thought that the game was merely a metaphoric vertical climb up Mount Olympus till the end of the game (it's not just vertical). If you make it further along, you eventually come across stores and everything is terribly expensive and items don't really seem to amp you up in a meaningful way and don't really make much sense.

You feel weak, under-powered and overwhelmed.

It was at this point that young me turned the game off and went off to play Kid Niki Radical Ninja. But modern me wanted to figure this game out. It turns out I should have kept playing. Pretty quickly I made it far enough to hit a horizontal level. My shot range increased, I started to power up. Like Metroid, the enemies in KI don't necessarily get harder as the game progresses, there's just more of them. By the late game, you're so powerful that what used to terrify you, you can handle with confidence. The feeling of empowerment is pretty cool.

What really surprised me about KI was not the vertical and horizontal levels, but the Labyrinths. I feel like this is where the game really comes together. You go back to being under-powered in the Labyrinths, but the combination of the exploration really makes these levels feel like a mini Zelda-like action RPG inside of the rest of the game -- or at least like Zelda's dungeons. The feel far more sophisticated than an early NES game has any right to feel.

|

| Was this... |

|

| The inspiration for the Labyrinths? |

Even more innovative, while wandering the dungeons, you can smash open statues to recruit helpers for the upcoming boss battle. They're not as decisive as I would have hoped, but the idea of playing a 1986 NES game with AI bot companions is pretty awesome, and they make you feel really ready for the boss battles, despite being powered down for the Labyrinth.

Finally, if you make it through the final and most challenging massive Labyrinth, you're rewarded with a great horizontal shmup level. It was a huge surprise to me and put a broad smile on my face. And it's this huge variety of KI that I really found remarkable. What I first thought would have just been a vertical climbing slog with an overamped difficulty level turned out to be a game full of almost Contra-like variety and play styles.

This game is pretty long for the time period and considering it's not an RPG. A quick run through by somebody who knows what they're doing takes about an hour and a half. Along the way there's some decent music -- nothing earth shattering, but welcome cheesy adventure accompaniment. There are plenty of fans though, and it hasn't stopped anybody from making cover version of some of the songs.

Graphics are actually pretty good for the time -- they don't hold up terribly well today, but characters have a definite cartoony feel and there's lots of effort put into giving them personality. What's lacking are background graphics, you play against a solid background for the vast majority of the game. It's fine in the way that this is fine with Metroid, but it's definite reminder of the age of the game.

Controls are pretty tight. Pit, your character, goes pretty much exactly where you ask him to. It's typical Nintendo polished play control. I have a few minor quibbles with platform hit detection, and jumping while aiming up, but on a game of this vintage it's excellent.

Despite being a popular, polished game, Kid Icarus has a more difficult legacy than Metroid. It got a Game Boy sequel, which improved on the formula in many ways. And Pit appeared in numerous Nintendo promotions. There's been a port of the original to the GBA, and a 3D Classics port (with some fixes for the controls), But that's about it. It even took an independent studio, risking the wrath of Nintendo's legal team to release a 16-bit style sequel.

Nintendo left this franchise on the shelf, basically to rot, generation after console generation until finally releasing a much praised 3DS game. It sold pretty well, but Nintendo, bizarrely has decided to back burner the franchise again. Considering the opportunity to add essentially all of a modified Greek pantheon to their IP stable, the decisions to not breath constant life into Pit is head scratching.

Given all that, I'm glad my initial impressions were wrong, I'm now a Kid Icarus fan.

Friday, March 14, 2014

Rock n' Roll Racing - Super Famicom/SNES

Let's be honest, until at least Ridge Racer on the PlayStation, 3d-style racing games were mostly derivative, definitely haven't aged well and most honestly weren't very good. It really took the jump to fully modeled polygonal tracks and cars to break the "driving towards the apex of a triangle" sameness that many early racing games suffered from.

|

| This view of racing was largely unchanged for years |

Sega, of course pushed this view of racing to impossible extremes with their Super Scalar sprite scaling technology and tried to fake a true 3d experience for years -- eventually even replacing the road triangle with dozens of quickly scaling sprites. Even Taito's fabulous Night Striker pushed the concept about as far as it could go.

It was obvious, even in the mid-80s that this approach was an evolutionary dead-end for racing games, but technology simply couldn't offer a more realistic experience. One alternative, the top-down racer like Atari's 1986 Super Sprint.

|

| An alternate view of the world. |

The technical barrier to making these kinds of games fun and good looking is much lower -- and I think that means that the developers had more time to tweak the game mechanics and add things like power ups and racing physics to the mix. To help give the games a little graphical boost, a common variant was the isometric racer. Unlike isometric platformers or puzzle games, this view actually works, and it works really well.

One of the earliest of these was Racing Destruction Set (RDS) on the Commodore 64. Which, while a fine game for 1985, didn't really create an immediate impact. However, it set the template for how an isometric racer should work. By zooming in on the action, it limits the view of the course. Since you are no longer an omniscient god with a view of the entire track, some of the tension of a first-person racer remains -- you don't see where all your opponents are all the time. It also introduced a combat system that made the game more than just running flat out till the end of the race.

In the arcades this was ignored and we ended up with 1989s Ivan "Ironman" Stewart's Super Off-Road. While fun, it was clear that it lacked the deeper strategy of an isometric combat racer, and it moved the viewpoint back out to a single screen overview of the action.

However, in 1988, these lessons weren't lost and we got one of the most popular isometric racers of all time, Rare's R.C. Pro-Am.

R.C. Pro-Am (RPA), proved that RDS's template for how an isometric racer should work was the right one.

Fast forward a few years to 1991 and it's time to make a racer for the SNES. At this point, despite being one of the most powerful home systems at the time, the choice for making a racer were pretty much driving into a triangle or yet another F-Zero/Super Mario Kart clone -- and there are tons of each. Looking back a few years, developers Silicon & Synapse realized that a third, mostly ignored option existed.

Reaching back more than half a decade, they realized that a modern (for the time) isometric racer might fit the bill. They decided to combine some of the slick breeziness of RPA with the deeper play mechanics of RDS and ended up producing RPM Racing. RPM is a good game, but it just doesn't really have a voice. Despite being one of the only racers of it's type, it doesn't stand out in the crowd.

Still, they were on to something, the formula was just off a bit. In a weird example of where the marketing department actually helped product development, the idea of using licensed rock music in a RPM sequel was hatched. Add in a bit of 90's "'tude", speed it up a bit and we get the excellent Rock n' Roll Racing (RnR).

One of the first things you notice about the game is the amazing renditions of popular rock songs. The work that went into bending to the SNES sound chip to produce such excellent tunes remains one of the high-points of SNES sound design. Hammond B3 organs, rock drum kit, bass and wailing guitar solos are all intact. It really wasn't until optical disks became the norm for videogames that a better sounding rendition of these songs could be heard in a game.

It's also a virtuoso example of how much better games sounded on the SNES vs. the Genesis. Despite a noble effort, the Genesis port of this game just doesn't have the same feel because the music doesn't push the pace along in the same way. To be honest, I quite often just kept playing because I wanted to know which one of the half-dozen tracks would be next.

And I think it's this amped up music that forced the designers to push the game's pace along. The almost lethargic RPM Racing turns into a frenetic, pedal to the metal rush in Rock n' Roll Racing.

Game mechanics-wise, there's really nothing surprising about RnR. You drive in a race with 3 competitors, firing weapons and dropping mines. Finish in the top 3 and you collect purse money you can put towards upgrades for your car or even buy a new car (better cars are unlocked as the levels progress). Tracks get harder as the game moves on and your opponents are upgrading just like you. Knowing when to buy an upgrade and when to save for a more expensive purchase it part of a fairly deep strategy system.

Game mechanics-wise, there's really nothing surprising about RnR. You drive in a race with 3 competitors, firing weapons and dropping mines. Finish in the top 3 and you collect purse money you can put towards upgrades for your car or even buy a new car (better cars are unlocked as the levels progress). Tracks get harder as the game moves on and your opponents are upgrading just like you. Knowing when to buy an upgrade and when to save for a more expensive purchase it part of a fairly deep strategy system.Combat is pretty straight forward, you can fire projectiles, drop mines or boost your speed temporarily. The specifics of the weapons vary a bit depending on which car you are upgrading. You can also upgrade your engine, traction, armor etc.

One of the really great things about RnR is the smooth and continuous progression of difficulty through level design and the constant upgrading of your opponents. Controls are spot on. Power slide around corners, or as you upgrade your grip hit a racing line, it's almost effortless. Weapon usage is simple and intuitive.

One of the really great things about RnR is the smooth and continuous progression of difficulty through level design and the constant upgrading of your opponents. Controls are spot on. Power slide around corners, or as you upgrade your grip hit a racing line, it's almost effortless. Weapon usage is simple and intuitive.About the only negative I can say about the racing experience, and the only point where I hit some frustration was lining my vehicle up in the isometric perspective to make a jump, only to land off the track and lose a few seconds -- or the race. This happened numerous times and I never seemed to get any better at it. Most of the time it's not a problem, but a few tracks are designed to make this a challenge.

Graphics are pretty good. They may not be the best the SNES ever saw, but they're a clear upgrade over RPM and have a sense of style and direction. Vehicles are cool and muscular monster trucks and aerodynamic tanks, tracks have spikes or Giger-esque biomechanic stylings. The art direction is solid and nothing detracts from the game.

Sound effects are a mixed bag, but to be honest, you'll be so busy racing to the music that it doesn't really matter much. This is an approach I think that was later copied by games such as Wipeout and Ridge Racer.

RnR is much loved but it's had troubled offspring. What seemed ripe for formulaic sequels simply didn't get any. Rock and Roll Racing 2 for the Playstation was kind of an unremarkable dud that like many early 3d games hasn't aged well at all. However, a spiritual copy, Motor Rock, is a love letter to the original and I highly encourage players looking for a modern take on RnR to get it if you can hunt it down. It nails everything about what made RnR special.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.png)

.jpg)