This is a mirror of a retrospective review I wrote on another service

two analog controllers

various peripherals like a gun controller

interchangeable game cartridges

even the potential to enhance the system functionality via advanced circuits in the cartridges.

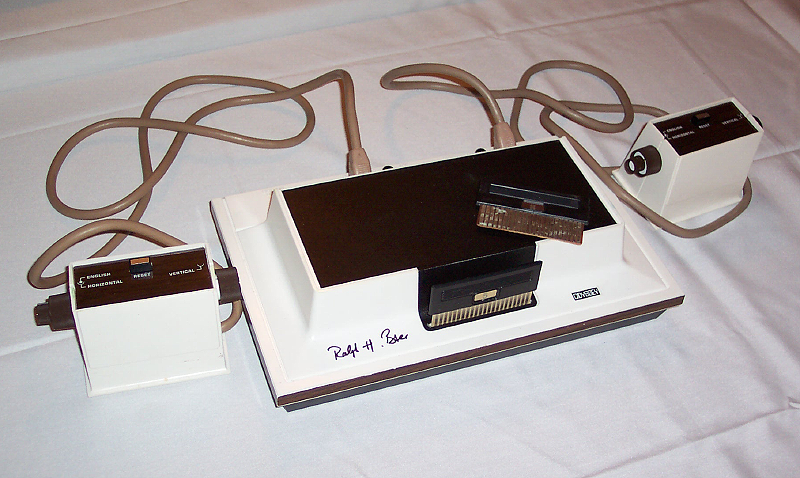

Considering this is 1960s technology with very few prior concepts to work off of, the inventor of the Odyssey, Ralph Baer (along with help from Bob Tremblay, Bob Solomon, Bill Harrison, John Mason and Bill Rush) must have built a time machine first because these ideas virtually defined home video gaming for the next three decades.

(An incredibly detailed history of the development of the Odyssey can be found here.)

Going to market, the Odyssey tapped cleanly into the sci-fi zeitgeist of the time. It looked just like a piece of tech out of the 2001 movie released just a couple years before.

At first glance, the story of the Odyssey seems to define an entertainment device that any modern gamer, young or old, would recognize. But digging deeper there are some major differences in both the technology and the business model behind this device.

The Technology

The first thing that a modern gamer might notice is that all of the games require a second player. Even games we might otherwise consider "single player". This is because the Odyssey doesn’t have a CPU! That’s right, there’s no central logic in the system. In fact, most of the system uses discrete circuits with fewer than 40 digital transistors in the entire device! The second player then acts as the CPU and performs various odds and ends from moving characters around to acting as an AI depending on the rules of the game.

The second noticeable difference is that the games essentially have no "graphics". What I mean is that screen characters are basically limited to two large blocks, a small block and a vertical bar depending on the cartridge. There’s not really such a thing as game resolution or color palette. There’s a simple collision detection circuit in the Odyssey useful for ball games like Ping Pong. However, the system has no ability to display numbers or text, so keeping score was entirely up to the players. Early prototypes were capable of providing some limited color, but the circuits were removed before production to save cost.

It’s clear that this limitation was well understood at the time as the system, and

It’s clear that this limitation was well understood at the time as the system, and later games, all shipped with clear plastic "overlays" that players were to place on top of the screen to simulate a better variety of game environments. Obviously inspired by board games, many of them provide simple set playfields for the user to move their character around often even included physical props to go along with the game.

Another obvious difference is that given no central logic unit to handle game rules, and no graphics, the game objects were more often just electronic props that the users could do with as they please, even invent new games. This could be considered a plus for a simple reason. The Odyssey actually was built with all of the games already in the device, the cartridges simply closed various discrete circuits and “activated” the appropriate game. An active imagination and a ready play friend could provide a great deal of playtime. The library was also expanded by using various cartridge and overlays to build up different games.

Oh yeah, and the system had no audio -- of any type. No beeps, boops, whistles, noise channel, nothing.

AND it ran off of batteries. Yes, batteries.

However, the main problem is that just like today, most of the games simply weren’t much fun. A game like States involved picking a card from a deck and moving the character block to where that state was on the map. Cat & Mouse simply let two players chase each other around the screen, but because there was no internal game logic, running outside of the play area, or over obstacles turns the games in a boring free for all.

This fact wasn’t lost on everybody. After seeing the Odyssey at a premier, and realizing that the Tennis and Hockey games were the most fun, Nolan Bushnell (father of Atari) went off and built Pong which went and kicked off the Arcade industry.

This fact wasn’t lost on everybody. After seeing the Odyssey at a premier, and realizing that the Tennis and Hockey games were the most fun, Nolan Bushnell (father of Atari) went off and built Pong which went and kicked off the Arcade industry.

Finally, the controllers are kind of...wonky. Today we take the concept of a combined control for the x & y axis for granted. The NES came with the now ubiquitous d-pad, the Atari VCS (2600) and other early systems had a joystick, and on and on. But the Odyssey has separate controls for the two axes. This makes learning to control the on-screen character very tricky, something like using an Etch A Sketch.

Despite all this, the Odyssey was the first, and without other’s mistakes to learn from, it was an amazing first attempt. Here’s a great video by the Smithsonian on the Brown Box and includes a cameo by Ralph Baer, the only person authorized to operate the device today.

The Business

The Odyssey was originally called "The Brown Box" after the fake wood paneling on the prototype unit used to demonstrate the concept. Original funded by a company called Sanders Associates, they realized, being a defense contractor that they had literally no business experience in consumer products. So they decided to license the technology to another company that did have this experience.

At first they approached the early cable television industry. The idea was to have the cable provider broadcast a fixed background that could be mixed in with the game objects to provide a more interesting playfield. Obviously this didn’t pan out -- hence the overlays. Eventually, the television manufacturer Magnavox took to the idea and licensed the technology. In the mix Sanders Associates and Magnavox ended up with a suite of key patents that earned them a great deal of licensing fees over the next few decades.

Interestingly, the cable idea is one that’s been tried in one form or another for quite some time (usually without much success)

This is where the business side gets a bit strange. Magnavox at the time sold their equipment through a direct sales channel – their own stores. This had some interesting side effects.

- Magnavox only showed the Odyssey playing on Magnavox Televisions in their advertisements -- leading the brand new video game buyer to think that the Odyssey only worked on Magnavox Televisions. Later home video game systems actually had to advertise that their systems would work on any home TV to overcome the public perception this built up.

- Training the sales staff was problematic. The sales models for Televisions and Radios is quite different from a video game system. You don’t just move devices, but you also push peripherals and games. Considering that the games were already in the device and all the cartridges did was "unlock"” that content. Moving cartridges was basically free money and the sales staff at Magnavox stores simply didn't push the games. More often than not, they simply left them boxed up behind the counter.

- The initial price point for the Odyssey, back when it was still a prototype, was $20 in the late 1960s or about $130 in 2010 dollars. The final price point when released in 1972 was $100 or a bit over $500 in 2010 dollars. Considering it was merely a curiosity, with few honestly interesting games, the Magnavox Odyssey sold well under half a million units (or put positively, successfully sold over 300,000 units in an entirely new market they created from scratch).

Conclusion

On the one hand, the Magnavox Odyssey set the stage for literally all of the rest of gaming since. On the other, it just wasn’t a whole ton of fun.

- Magnavox Odyssey System Review

- History of Video Games Pt 2 - Ralph Baer & Magnavox Odyssey (warning explicit language)

- Odyssey - AVGN - Cinemassacre.com (warning explicit language)

Or was it?

Playing Odyssey (Behind the scenes) (warning explicit language)

Behind the scenes, these perfectly modern gamers seem to be having a blast. It might be a booze fueled blast, but they're having tons of fun.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment