Many years ago, when Nintendo was still building out franchises, and before backgrounds became common things in NES games, they produced a reusable game engine. In the mid-80s (especially mid-80s Japan which still struggles with modern software practices to this day) this was pretty mind-blowing. This engine was used in two games, one of the two games, Metroid, has become the stuff of legends even spawning it's own game genre name. The other, Kid Icarus is no less loved, but has always sat in the shadows of it's big brother.

Kid Icarus, doesn't really do any of these things. You start weak, and enemies are thrown at you from the beginning. You collect hearts, but they don't restore your life, and you climb climb climb perpetually up. There are doors, but the first few you find don't really help you. The difficulty is relentless. My first couple plays, I died so early and so often I thought that the game was merely a metaphoric vertical climb up Mount Olympus till the end of the game (it's not just vertical). If you make it further along, you eventually come across stores and everything is terribly expensive and items don't really seem to amp you up in a meaningful way and don't really make much sense.

You feel weak, under-powered and overwhelmed.

It was at this point that young me turned the game off and went off to play Kid Niki Radical Ninja. But modern me wanted to figure this game out. It turns out I should have kept playing. Pretty quickly I made it far enough to hit a horizontal level. My shot range increased, I started to power up. Like Metroid, the enemies in KI don't necessarily get harder as the game progresses, there's just more of them. By the late game, you're so powerful that what used to terrify you, you can handle with confidence. The feeling of empowerment is pretty cool.

What really surprised me about KI was not the vertical and horizontal levels, but the Labyrinths. I feel like this is where the game really comes together. You go back to being under-powered in the Labyrinths, but the combination of the exploration really makes these levels feel like a mini Zelda-like action RPG inside of the rest of the game -- or at least like Zelda's dungeons. The feel far more sophisticated than an early NES game has any right to feel.

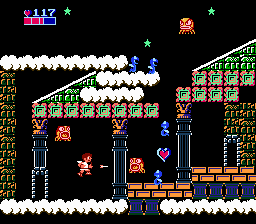

| Was this... |

| The inspiration for the Labyrinths? |

Even more innovative, while wandering the dungeons, you can smash open statues to recruit helpers for the upcoming boss battle. They're not as decisive as I would have hoped, but the idea of playing a 1986 NES game with AI bot companions is pretty awesome, and they make you feel really ready for the boss battles, despite being powered down for the Labyrinth.

Finally, if you make it through the final and most challenging massive Labyrinth, you're rewarded with a great horizontal shmup level. It was a huge surprise to me and put a broad smile on my face. And it's this huge variety of KI that I really found remarkable. What I first thought would have just been a vertical climbing slog with an overamped difficulty level turned out to be a game full of almost Contra-like variety and play styles.

This game is pretty long for the time period and considering it's not an RPG. A quick run through by somebody who knows what they're doing takes about an hour and a half. Along the way there's some decent music -- nothing earth shattering, but welcome cheesy adventure accompaniment. There are plenty of fans though, and it hasn't stopped anybody from making cover version of some of the songs.

Graphics are actually pretty good for the time -- they don't hold up terribly well today, but characters have a definite cartoony feel and there's lots of effort put into giving them personality. What's lacking are background graphics, you play against a solid background for the vast majority of the game. It's fine in the way that this is fine with Metroid, but it's definite reminder of the age of the game.

Controls are pretty tight. Pit, your character, goes pretty much exactly where you ask him to. It's typical Nintendo polished play control. I have a few minor quibbles with platform hit detection, and jumping while aiming up, but on a game of this vintage it's excellent.

Despite being a popular, polished game, Kid Icarus has a more difficult legacy than Metroid. It got a Game Boy sequel, which improved on the formula in many ways. And Pit appeared in numerous Nintendo promotions. There's been a port of the original to the GBA, and a 3D Classics port (with some fixes for the controls), But that's about it. It even took an independent studio, risking the wrath of Nintendo's legal team to release a 16-bit style sequel.

Nintendo left this franchise on the shelf, basically to rot, generation after console generation until finally releasing a much praised 3DS game. It sold pretty well, but Nintendo, bizarrely has decided to back burner the franchise again. Considering the opportunity to add essentially all of a modified Greek pantheon to their IP stable, the decisions to not breath constant life into Pit is head scratching.

Given all that, I'm glad my initial impressions were wrong, I'm now a Kid Icarus fan.