In any given year, as a consumer, you could chose from a dozen different incompatible but popular platforms and likely purchased, or pirated, software on audio cassettes for something right above pocket change. The market was so saturated that cassettes with dozens of games could be found at the supermarket checkout line for a few pounds and were often just included with magazines for free. It was such an amazing time that it even spawned a number of movies, one of the best is Micro Men -- a home rolled Pirates of Silicon Valley about a struggle between two computing titans that most people outside of Britain might not even be aware occurred.

In any given year, as a consumer, you could chose from a dozen different incompatible but popular platforms and likely purchased, or pirated, software on audio cassettes for something right above pocket change. The market was so saturated that cassettes with dozens of games could be found at the supermarket checkout line for a few pounds and were often just included with magazines for free. It was such an amazing time that it even spawned a number of movies, one of the best is Micro Men -- a home rolled Pirates of Silicon Valley about a struggle between two computing titans that most people outside of Britain might not even be aware occurred.

Curiously, the practical and cost conscious British market never really took to dedicated game consoles in those days. Sega's biggest 8-bit success was in Britain, but Nintendo and other players largely ignored the islands -- finding the saturated 8-bit computing market impenetrable. One story that's heard time and time again is that the computing revolution was promoted on national news, and concerned parents bought what they could to help their children stay on as players of this revolution they couldn't quite understand. Gaming was very much a secondary consideration in the minds of parents, but once in the hands of smart British school children who not only consumed, but produced games and a prodigious rate, it came to absolutely dominate the market.

This market, and the bizarre economics that it existed in and made it happen set the stage for an entire industry of literal bedroom software developers. Mostly in the teens or early twenties, they often contracted out with early software publishing houses who then shipped the product out to various sales channels or looked for magazine promotions to take part in. The competition was impossibly fierce - fortunes were won and lost in mere months.

Eventually this market fell to newer Amiga, Acorn and Atari 16-bit computers, then finally IBM PCs and Japanese gaming consoles. Today the British computing market is a mere shadow of what it once was, but it's been carefully chronicled and documented in numerous books and perhaps best by youtuber Kim Justice.

Out of this legacy sprung several legendary software houses. One was Bug-Byte Software, most famous for British killer-app Manic Miner. From Bug-Byte sprang Imagine Software -- which eventually collapsed like many other companies of the era. From those ashes sprung a couple of other software houses, the greatest of which was Psygnosis. Recognizing the potential for the new 16-bit machines then coming on the market, and having been able to make a clean break from the impossible 8-bit market, Psygnosis dove in and started producing and publishing games.

A hallmark of Psygnosis games was absolutely fantastic, often jaw dropping, graphics and artwork. From the logo to the box art, Psygnosis pushed the power of their new platforms to levels very few other publishers were able to achieve -- often showcasing rock album like box covers, special guest composers and even financing the art production on games made by single developers. Often, the incredible promotional artwork had nothing to do with the games' graphics, but it challenged the market and in many ways harkened to the fanciful promotional art on earlier Atari VCS games -- a technique which moved millions of games in the U.S.

Another hallmark of Psygnosis published titles was a brutal, often nearly unplayable, difficulty. The hallmark game, Shadow of the Beast, moved hundreds of thousands of not only games, but entire computers as it was so beautiful it frequently demoed in computer stores. But it was so hard to play that most people gave up quickly, pulling it out only to show off their machine's power. While some of Psygnosis' more popular games found their way onto game consoles -- usually the Mega Drive, they never became the kind of popular classics on those platforms that they did on the home computers. I think this is an inheritance from the 8-bit days, a "get it out the door and into the store" philosophy, that produced less balanced and polished games than the more thoughtful Japanese imports.

| An example of the incredible Psygnosis box-art |

Nevertheless, when Sony decided to get into the gaming market after a failed partnership with Nintendo, they looked around for well known software houses that were neither loyal to the entrenched Sega or Nintendo console markets. A natural place for Sony to look was in the computer gaming markets, but fussy and slow simulation and adventure games dominated most of the American market. The British market on the other hand, going back to the 8-bit days, used their computing platforms as port targets for arcade and other console games - often furnished by U.S. Gold or Ocean software. However, Sony needed original titles that fell into the style of gameplay the home console market demanded and Psygnosis fit the bill.

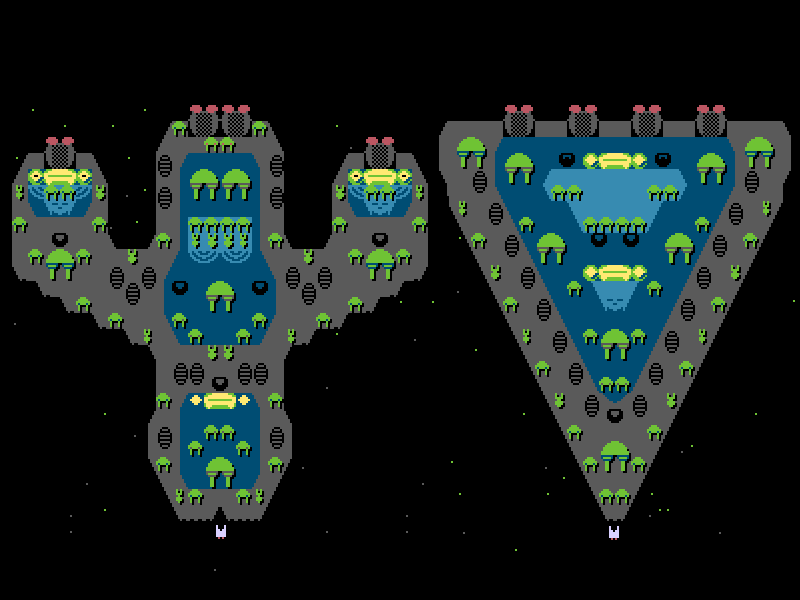

| WipEout |

In 1993 Sony purchased Psygnosis and put them to work making games for a single reference platform, the soon to be release Sony PlayStation. While many people feel that Psygnosis' original 16-bit computing run was it's golden period, I think this mid-90s PlayStation run was where the development teams the company managed really hit their stride: Colony Wars, Wipeout and G-Police all came out during this time with Wipeout pretty much revolutionizing console racing. This time though, the company's attention to art and audio, and Sony's insistence that the gameplay be worked out, payed off and Sony came to be a dominant force in the home console industry - with Psygnosis at one point selling 40% of all video games in Europe. (An interesting side note is that this basic strategy was almost exactly what Microsoft later followed with their Xbox console and the purchase of Bungie software, makers of Halo).

During this era, Psygnosis was highly prolific, and several of the games from this time have all but been forgotten. One of which is finally the subject of this review: Assault Rigs, released in 1996. Taking a step back, I first played Assault Rigs on my IBM PC, off of a budget disk I picked up at a local computer superstore. I was very immediately taken in by the energetic gameplay and Tron-like graphics in the early levels, but felt like the game was a bit out of place as a computer title. Soon I bought a PlayStation and found the game available there in the original and on that platform the gameplay made a lot more sense.

Keeping in mind that by 1996 the idea of a first (or third for that matter) person shooter was still fairly new, Assault Rigs is pretty remarkable. By sticking to a relatively safe genre, Psygnosis was free to innovate on their new Sony platform and polish up the game. Still it has some odd mid-90s bits that make it feel like it was never meant to be a triple-A title, but the also-ran that history has left it as. For example, maze textures often feature random logos -- huge mouths, or game titles -- and weird audio clips sound off all littering the levels with a constant sense of being very out of place and inexplicable. It can maybe only be attributed as an expression of Sony's marketing around mid-90's "'tude".

The tanks are hover tanks and while featuring classic pre-Mario 64 "tank controls", can also strafe and launch off ramps in well controlled briskness. There's some lack of polish on collisions with walls, making it hard to get up to the kind of frenetic game-play a Quake of the time would ensue. Some reviews complain about the camera, but I never found myself spending lots of time upset about it.

What I did find frustrating was the very unpredictable damage model on enemies. In a firefight some enemies would go down after a couple hits from my main gun, while other times I'd pound away at them dozens of times while my shields were rapidly draining before they, or I, finally died. However, there's many other weapons to be found around the map, from a minigun to a first person guided missile, the upgrades are fairly fun and bring variety to the gameplay.

The gameplay is finally where Assault Rigs is the most interesting. Today we might call it an "over the shoulder third person combat collect-a-thon puzzle platformer" and that genre fitting title basically describes what the game is. You have to navigate your tank around increasingly large and complex environments full of moving platforms, enemies and pickups. The goal is to collect a certain number of jewels then make your way to an exit. Destroying all of the enemies isn't a goal and isn't important, if you can get around the enemies without a fight, it's better in many cases. Later levels turn into intense puzzles. However, the lack of indication for what you're supposed to do, and any sort of mapping option does leave the player fairly disoriented. The skill ramp up is reasonably smooth, but I think the best of the game is the breezier levels at the beginning. But I'm also not much of a fan of puzzle platformers so temper my opinion with that knowledge.

Contemporary reviews of the game often lamented the poor fit of the music to the gameplay. But I think if you consider the hodgepodge of other audio-visual inputs, and the goal of the actual games, the lack of fit actually makes it seem to fit better. The music ranges from techno to light jazz to rock-funk and most of it is quite listenable for what it is. I never went looking for an option to turn the music off.

The game didn't leave much of a legacy, there's only a handful of gameplay videos on youtube for example. It did find it's way to the PC and the Sega Saturn eventually, but that's it. It's one of those solid B-grade games that's fun enough to play, but is just average enough that it gets lost among both better and worse games. Still it's an interesting footnote in history, a minor release from a major studio right near the start of the 3d-gaming revolution. Mario-64 would come out the same year and completely change how 3d platform games were thought about and played. Still, for a tank-controlled 3d platformer, the designers worked within that world and produced a fun diversion for a while. Once you tire of it, you won't feel bad putting it down, but you'll think fondly of the few hours you did spend with it.